Sunday, 22 September, 2024 – Monday, 30 September, 2024

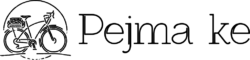

The day arrived when we were finally about to cross into Mexico. We would cross the border in Tijuana, then cycle down the Baja Peninsula, which is mostly desert with rare towns. It’s the part of Mexico that is the most American-like; a lot of US tourists come down this way, and a lot of people should be speaking both languages—Spanish and English. Were we nervous about it? Of course we were; because of all the mixed opinions about the country, we had no idea what to expect. But three things helped us cool down our nerves:

- Andrew was taking us to the border with his van, and he was also crossing into Mexico, so we wouldn’t have to do it alone and we wouldn’t have to figure out everything on our own.

- We had an apartment reserved in Rosarito, about 30 kilometers south of the border. This way, we wouldn’t have to worry where we could safely sleep for the first night (we paid around 65 euros for it).

- And finally, the best thing was that Andrew contacted his buddy Alan in Tijuana, and they organized a group ride from Tijuana to Rosarito. We were about to have some guides show us how to deal with Mexican traffic.

First, we met Roni (Veronica). She came to Andrew’s house and joined us in his van, going to the Mexican border. We left the van in the parking lot and cycled to the pedestrian border crossing. Getting our bicycles through small rotating doors wasn’t easy, but we managed to do it by lifting the first tire a little bit and slowly turning the gate.

When planning our trip, we found out that with a Slovenian passport, we could get a Mexican visa for up to 6 months and that you do this directly on the border (together with paying a “small fee” of around 35 euros per person). So we expected that everything would go smoothly, but we were mistaken once again. It all started with an officer at the border writing the wrong passport number on the application. Luckily, we paid close attention to everything because if something went wrong, we would be the ones having trouble leaving Mexico, not the officer who wrote it badly. After fixing that, we explained that we would cycle across Mexico and would need a 180-day visa. This took the officer by surprise, and he said that he could give us only a 7-day visa or that we should come some other day. I didn’t know that we were bargaining about the length of our stay, and I for sure wasn’t as comfortable in our ability to cycle Mexico in 7 days as the officer was. He said that “the system” won’t allow him to give us a longer visa. Naturally, we couldn’t accept only a week in Mexico, so he called someone more experienced to solve the issue. It took a few more “call more experienced officer” until, at some point, 4 officers were looking at the screen and one of them managed to fix “the system” to get us a 6-month visa. It seemed as if a 7-day visa was just easier to do and nobody had the patience to type in everything needed for a longer visa—”the system” won’t let them do it. When we finally got a valid visa and we paid for it, they showed us to move on. I don’t know what they were expecting, but it for sure wasn’t the fact that we needed TWO visas. Why would we? After all, it was two of us with two bikes and two passports. As if Iris was just casually hanging there to pass the time. The officer wasn’t pleased with the fact that he would have to do the whole process one more time.

“Gracias señor” was the best Spanish we could scramble together, then we went on. The next part of the border crossing was going through a security check, but the officers there were having a break on their chairs. We, together with our fully loaded bikes, looked like a lot of work, so they didn’t say anything when we just walked through the beeping metal detector and completely avoided the x-ray device. Neither we nor the officers there wanted us to take everything apart, put everything on the conveyor belt, then take everything out of the bags if they desired so, and finally pack everything back on the bikes. Honestly, we were a little bit surprised at how easy this “security check” was, but we weren’t going to complain; after all, we already spent too much time getting the visas. During our wait for visas, Lane joined us, another cyclist for our ride.

On the other side of the border, we went into the shadow and waited for Alan to join us. In the meantime, it was interesting to watch how taxi drivers yelled at potential customers coming through the gates, offering their services. We also saw that money exchanges there had a better exchange rate for pesos than the one we got in San Diego. After meeting with Alan, we headed west, close to the border, to the playas (beaches). We met with the rest of the crew (on the way) there: Emmanuel, Santiago, and Raul. So, all together, there were 9 of us! This was the first time on our trip that we would ride in a group, an experience we were excited about.

With local riders comes also local knowledge of the roads; it was amazing to just lay back and cycle without worrying about navigation. It started with smaller roads, but at some point, we had to climb over the fence to get on the toll road, which is officially not meant for cyclists, but it has a wide shoulder—a luxury that a regular road doesn’t offer. All in all, the experience was amazing. Would we do it again? I think so, but we have no idea how boring the ride was for everyone else who had to go with our speed. It might have been interesting because it was something unusual, but on longer rides, something like this probably wouldn’t be possible.

We can’t thank enough everyone who joined us and made our first day in Mexico unforgettable. We couldn’t ask for a better welcome into the country, and the company that Andrew and Alan gathered was amazing. When we arrived in Rosarito, we went to a taco place; we tried some spicy Mexican food (and regretted it), and after knowing most of our company for only a few hours, it was already hard to say goodbye to everyone. All of them still had to cycle back to Rosarito, which was another 30 kilometers, but this time, they didn’t have our slow asses with them. We, on the other hand, had to find the apartment that we rented, then we had to plan ahead. We were once again on our own.

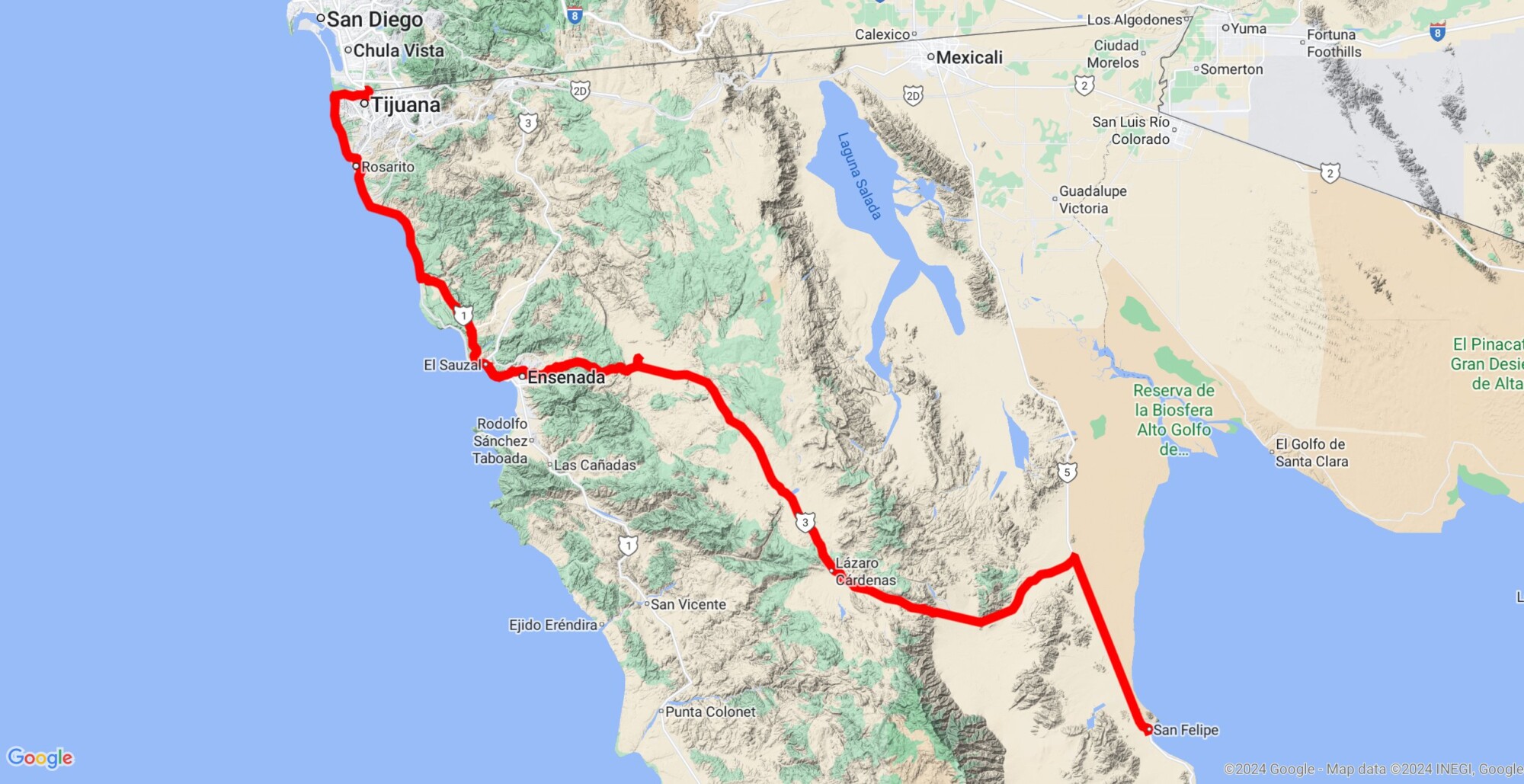

Why did we decide to get an Airbnb apartment instead of a hotel or a hostel? Well, we didn’t want to go to the hostel because not all of them have a place to store our bikes. And for hotels, we found a lot of reviews online, claiming that the rooms they got were dirty and moldy, and hotels would cost us more than this apartment did. So it was an easy choice; we just regret that we didn’t book it earlier because the price already went up around 15€ between the time we found it and the time we decided to book it. Nevertheless, having this place was definitely the right decision. Trying to find a place when we were already in Rosarito would be harder, and every blog that we read about cycling south through Tijuana advises not to camp outside for the first few days because you’re still too close to the border.

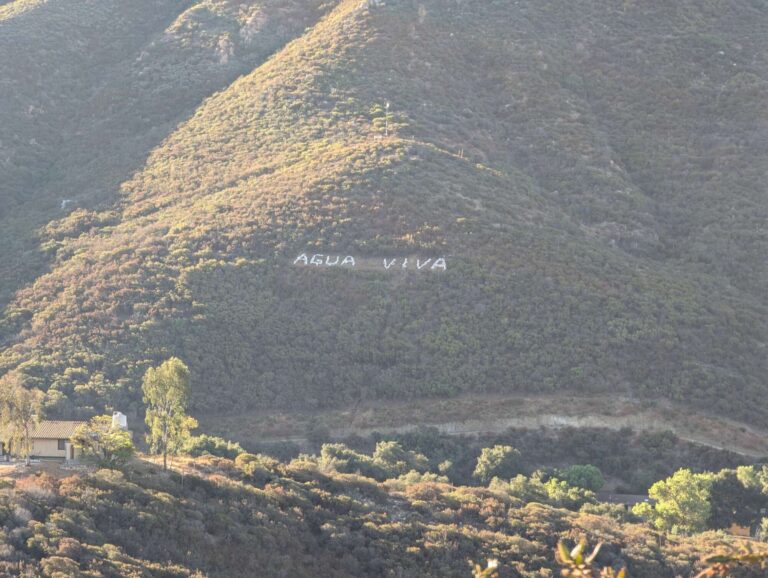

There’s one thing about Mexico that we didn’t plan for: we would have to buy all the water because the one from the tap is not drinkable. Even locals buy their water, but luckily, it’s usually very cheap—between 0,05€ and 0,10€ per liter. The main places that you want to look for to buy cheap water are Purificadoras. You can usually recognize them by the blue-colored buildings or big water tanks outside, and they sell purified water.

We can’t complain about our Airbnb apartment, even though it was more on the modest side: bed, couch, toilet, shower, tiny kitchen, and two chairs. We haven’t seen many slim Mexicans, but the chairs in the apartment were apparently meant for them; when Primož sat on one, it bent. So we only had one usable chair. Also, the bedframe was barely holding together; someone before us wasn’t very gentle. But at least it was clean (after all there wasn’t much to clean), spacious enough to bring our bikes inside, and we felt very secure behind a high fence around the property and one more on the apartment door. We did our laundry, took a shower, and cooked some food. We also boiled a pot of water to use it for tea and brushing our teeth.

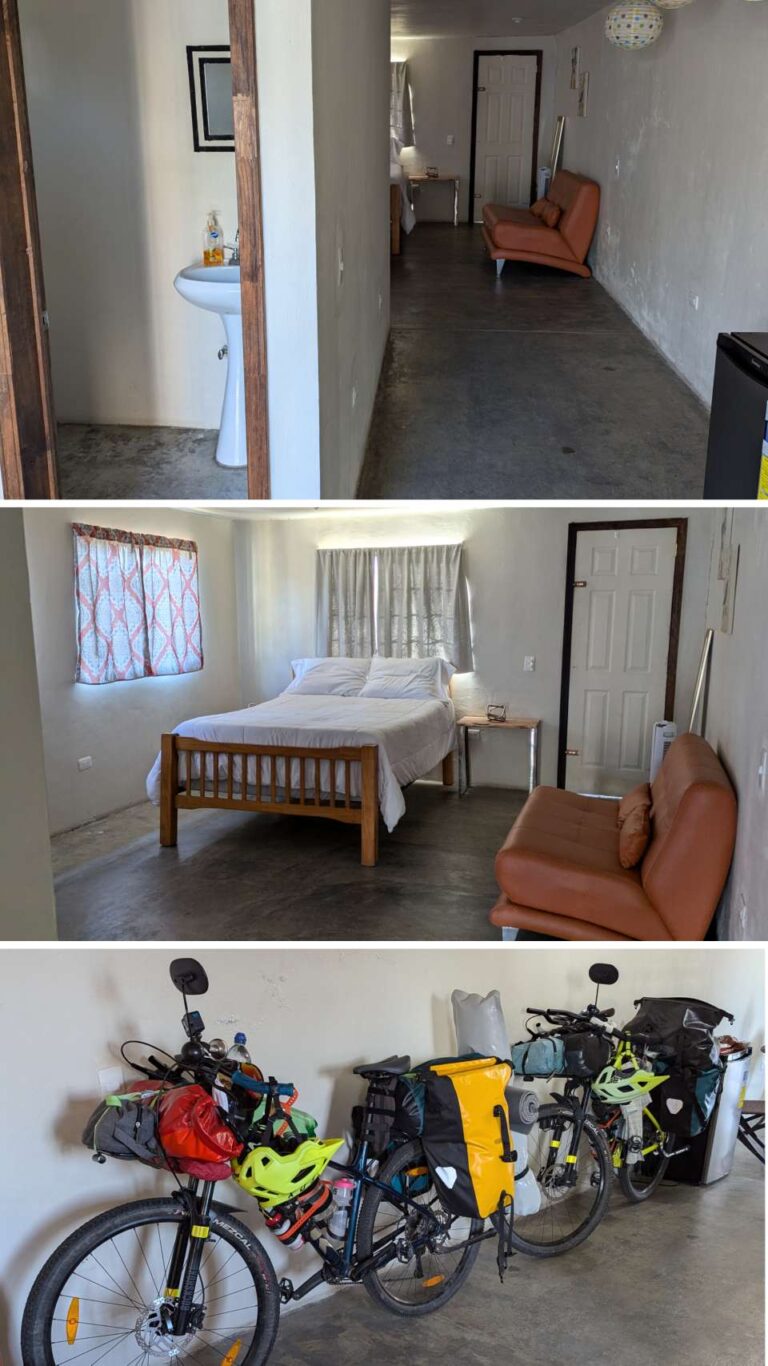

The next day (day 91) was our first real experience of Mexico. Our navigation took us on some smaller streets in the city, and we were shocked by the amount of trash next to the road and by the fact that as soon as you leave the main road, nothing is paved anymore; it’s gravel if you’re lucky, otherwise it’s sand. We take back everything bad that we’ve said about Italy.

As soon as we left the city, the shoulder on Mexican Highway 1 disappeared. At least we had a nice view over the ocean that was around 5–15 meters lower than us. Our plan was to cycle around 35 kilometers to La Mision, where we would try to find a quiet and remote place on the beach to stay overnight. But when we got there, everything was very open; one could see across the whole beach. We checked the iOverlander application, and we found a campsite where we could potentially stay for cheap. It was just a huge parking lot next to the sea, and it was mostly empty, so we stopped there and asked for a price. At first, they asked for 250 pesos, but after some negotiation in English (combined with some Spanish words), we managed to get the price down to 200 pesos, which is a bit under 10€. We set up a tent close to the cliff, cooked a lunch, met a chipmunk that kept coming to us for food, took an afternoon nap, got a plate of grilled meat from neighbors in camp, and just enjoyed the fact that we had a safe sleeping spot one more night. In the morning we got up early and quickly packed because other neighbors started a fire and smoked us like bacon.

There aren’t many WarmShower hosts in Baja, but we managed to find one close to Ensenada, and getting there was our goal for day 92. We’d heard that passing Ensenada would bring us into the real desert, but already on the way there, the nature around us started to look like wilderness. There were long straight roads with not much beside them; the nature was dry, and there were a lot of crosses by the road, supposedly from fatal road accidents. Also, there was a ton of trash everywhere by the road; it looked as if people just threw it out of their cars while driving. What’s especially concerning is the number of empty beer cans that you can find next to the road; they might contribute to the number of crosses that we saw. In the afternoon, we met with Jesse, our host for the night. Besides the talking and the dinner that we had, he showed us some amazing harmonica playing, and he inspired us to take out our harmonica more often and try to learn it.

On the morning of the following day (day 93), we visited our first Purificadora which was close to Jesse’s house. We paid 10 pesos (around 50 cents) for 10 liters of water, and we had to improvise a little bit about how we would carry this much water on our bikes.

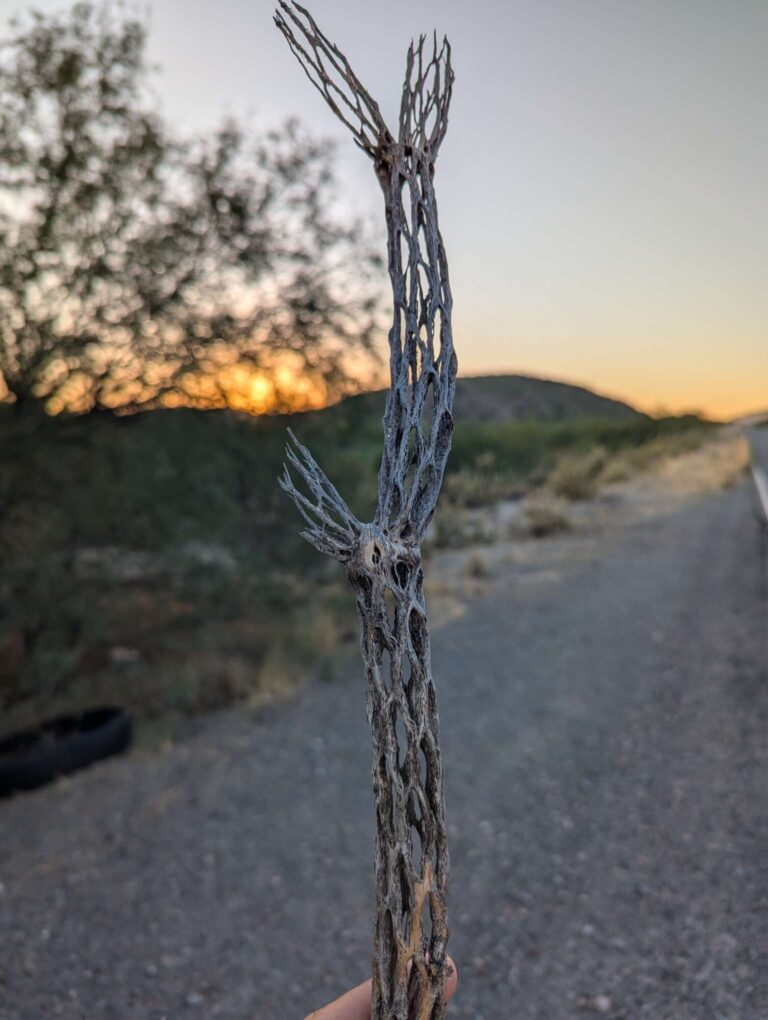

Crossing Ensenada was terrible. Komoot took us into some poor part of the city without any proper roads and with very very steep hills. After a couple of those, we decided to just take the shortest road to Highway 3, then follow it out of the city. On the way to the highway, we had to cross a hill so steep that both of us had to push a single bike just to get up the sandy road. We knew that going east of Ensenada we would have around two days of riding uphill. From sea level, we would have to get to around 1200 meters of height. But even though it was mostly uphill, the road wasn’t very steep; around 1-2% for the next 90 kilometers. We saw our first cactuses on this part of the road.

After 30 kilometers, we stopped next to some ranch/camp called Quinta Paluvik, unsure if they were open or not. A man came out, but he only spoke Spanish, and we only spoke English. So, it was time to test our broken Spanish. Puedo dormir aqui? (Can I sleep here?). Cuanto cuesta por noche? (How much does it cost per night?). He asked for 30$. We didn’t know how to bargain in Spanish, so we just talked to each other in Slovenian for a bit, then said 200 pesos. He looked surprised, and he laughed at us, but eventually he accepted the offer. It probably helped that we were the only guests. We set our tent under the roof on the terrace, and we even found some electric outlets to charge everything. The two dogs that were guarding the camp came to us while we were eating, begging for some food.

On the next day (day 94), we climbed the rest of the hill. We were passed by a full convoy of military vehicles on the way, but even though they looked terrifying, some of them waved at us when we stopped by the road. When we crossed into Tijuana, we already saw a few vehicles filled with soldiers, but we were seeing more of them as we were approaching Ojos Negros. It turned out that there was a military security checkpoint on the road before the town, and we didn’t know what to expect out of it. Just to be on the safe side, we took our GoPro camera off the handlebar and took off our sunglasses to look more friendly. They just waved us through; we didn’t even have to stop. But there was also a truck filled with hay cubes, and one soldier was poking inside with a long stick. We’re still not sure what they were looking for or why they’re even there. But on the way south, we will see such points a few more times.

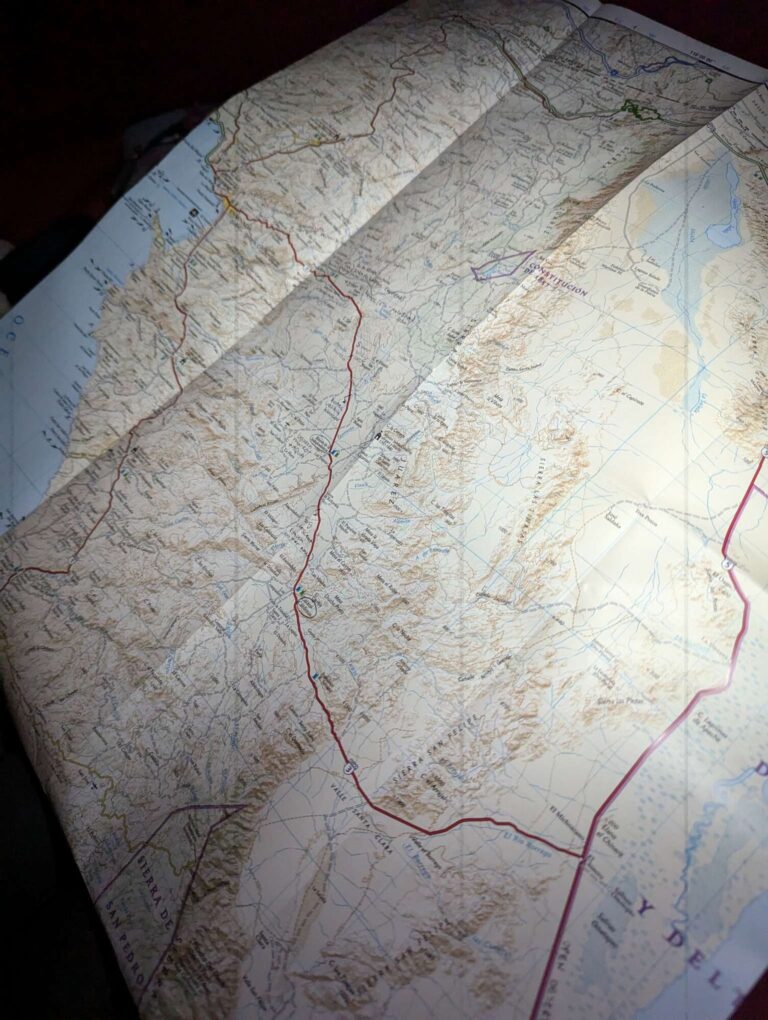

We made a small detour off the highway to get water in Ojos Negros. One must use every opportunity to get water because it’s very hard to tell when the next one will come. Ever since we left Ensenada, we lost phone signal, so we had to rely more on a paper map and the iOverlander app (which works without the internet). Near the top of the hill, we had a long break next to the road, and we decided that we would sleep there. It was late afternoon, and we still had a couple of hours before the darkness, so we took out our Spanish book and tried to learn a few new words. In the meantime, several military cars passed us, but the highlight of the day was when a car with an older couple stopped across the road. A man stepped out, took a bag, opened a car trunk, and called Primož over. It turned out that they had a full trunk of raw sweetcorn, and he filled up a bag of it for us. Our Spanish wasn’t on the level of saying “That’s too much corn for us”, so we just took the bag, asked if we needed to bake it (fuego = fire), and then we thanked both of them for their kindness (muchas gracias, señor y señora). Now, what can we do with 2 kilograms of raw sweetcorn? We would love to make a fire and bake it, and we already started to gather some wood. But because of the regular military vehicles, we decided that it was not a smart idea to make a fire in a desert and attract unwanted attention. So we peeled a couple of corn, picked them into our pot, and cooked them for around 10 minutes. The result was delicious! We haven’t eaten the corn that sweet before. We ate some with the spoon and stored the rest in our Tupperware box for later. It looked like we would eat cooked corn for the next few days.

The day was so hot that we drank around 4 liters of water each, but that night was cold—probably the coldest night on our journey. We were at an altitude of 1200 meters, and we were wearing most of our clothes. But the view of the night sky was amazing—so many stars and not a single cloud. And because we were so far away from any city, there wasn’t any light around us that would pollute the night sky. Our water in the morning was so cold that it seemed close to freezing. It’s too bad that we can’t store it and drink it during the hot day.

Day 95 was corny—we had corn for breakfast with crackers, for lunch with beans and tortillas, and for dinner with another round of crackers. Some more climbing uphill, then a very long descent on the other side of the mountain chain. The air was hot like in the oven, and it was burning us in the face while we were going downhill. One more reminder that we need to learn Spanish: while we had a break, a man in a car stopped and offered us a pollo, which we couldn’t understand. It was only after he left that we figured out that he was offering us a chicken! We don’t know if it was dead or alive, but either we would eat well or the chicken would because we still had enough corn to feed it for a few weeks.

We had two breaks that day because that’s all the shadow we could find along the way. But we also stopped a few times in the sun because Primož wanted to have pictures taken of him with different cactuses that we saw by the road. When we set up a tent that evening, we figured out that we passed the last spot to refill the water. We were deciding for the next day between going 7 kilometers back uphill or 50 kilometers of steep downhill with around 2 liters of water left. The problem with going back was that most places in Mexico don’t open very early in the morning, so we would have to do most of the riding in the heat of the day. But if we get up early before it gets hot, we would need around 2 hours for the downhill ride, then we could get water when the shop opens up. We agreed on the second option.

Day 96. That was the fastest and easiest 50 kilometers that we made on the journey, and we had them done by 9 AM. There was another military checkpoint at the intersection of Highways 3 and 5, and this time we had to answer a few questions. Where are you going? Why? All the way with bikes? Are your bikes expensive? Luckily, we didn’t understand the last question because the word ‘expensive’ (caro) is very similar to the word for ‘car’ (carro). So when he was pointing at our bikes and asking, ‘Caro?‘ we just insisted that that’s a bike and not a car. We have no idea why that soldier was interested in the value of our bikes, but he gave up after a few tries and let us go through.

On our paper map, it looked like there should be a small village near the intersection, but there wasn’t anything besides a single bar. So, we were forced to go ask to buy water there, and a man scammed us like a pro. We were almost without water, so we had to get it somehow. We asked to refill our water bottles; he agreed and asked us how many liters. We said nine, then we went outside to take all of the water bottles off the bikes. When we came back in, he insisted that he didn’t have any other water than the bottled one (despite having the pipe on the wall), and he put nine one-liter bottles on the counter. How much? 230 pesos. Iris gave him 250 pesos, expecting to get back some change, and in the meantime, the man changed his mind and asked for 280 pesos. We had no other option, so we paid 14€ for 9 liters of water. For that much money, we could get over 300 liters of drinkable water in any purificadora.

The day was hot, and we took a long break under the highway bridge near the intersection. We got a phone signal for the first time after 4 days, so we updated our Instagram, then we spent the time writing a blog, eating, writing a diary, and talking about our plans for the future. We also put out our solar panels to charge the powerbank on the sun. A few hours passed; we saw a snake in the meantime, then we decided to continue in the afternoon. We went through another security check, this time on Highway 5, but they just waved us through. After almost 20 kilometers, we decided that it was enough for the day; we found an appropriate place to set up a tent a bit off the road. Just as we started to take the tent off the bike, we came to the terrible realization: we forgot our solar panels, powerbank, and frisbee 20 kilometers back under the bridge! We had no other choice; Primož took everything off the bike and cycled back, hoping that nobody took our things from the side of the road. In the meantime, Iris had to set up our camp alone.

It was one time that we were actually glad that there was so much trash by the Mexican roads; no one took our solar panels, powerbank, and frisbee! They looked like another piece of trash someone threw out of their car. So, after almost 2 hours of extra cycling in the dark, Primož was back. We were once again low on water, but we would be in San Filipe on the following day, and we were already dreaming about cold drinks that we would buy. But that was the only cold thing. That night was among the worst ones on our trip; the temperatures wouldn’t drop under 30˚C, there wasn’t any wind, and the moisture in the air was high. I don’t know if we slept for more than 3-4 hours; the rest of the night was spent sweating and rolling around.

It was 5 AM on day 97, and we were already up. We had to do around 30 kilometers to San Felipe, each one having just over half a liter of water, and there weren’t any descents on the way. What was the biggest and coldest drink they had in the Calimax store? 3 liters of Sprite! It was the best Sprite that we had ever drank; it was so cold that it gave us brainfreeze, but we couldn’t care less; it returned to us our will to live. After some testing, we figured out that 3 liters of Sprite, without proper breakfast, can make your stomach hurt, but it was still worth it.

It was in front of Calimax where we met Valery and her mom Anna. They stopped and asked us something in Spanish, and it didn’t take much for them to figure out that we didn’t speak Spanish, even if we tried. Well, Valery was kind enough to give us her Instagram and wrote into Google Translate “Text me if you need any help”. Since we didn’t have any real plan of where we would sleep that night, we tested our luck and wrote to her, asking if we could come by in the afternoon and spend the night there. Sure enough, she responded that she would gladly host us!

In the meantime, we ate brunch in front of the store, then we went to purificadora to refill our water. And there was one more thing we had to do. You may wonder how we washed our clothes while cycling in the desert? To be honest, we didn’t. We didn’t have any excess water that we could use for that, so our solution was to wear one pair of socks and underwear while the second pair from the previous day was hanging on the back of our bikes, burning under the hot sun. It was a washer and dryer combined. With everything else, we just wore the same clothes every day. But we couldn’t go to Valery so stinky, so we found a laundry place where we paid 80 pesos (around 4€) for a full load of washing and drying of almost everything we had. It was an amazing deal.

We met Oskar in front of the laundry place. A kind man in his 50s, he lived in San Felipe for a year; before that, he was living in the USA, so we could talk in English. He loved our journey, and we loved the conversation we had. He invited us to stay at his place, but we said that we already had a “reservation” with Valery. We gave him our sticker so he could follow us, then he surprised us and gave us 1000 pesos! Not only was that a lot of money (50€), we were shocked that he wanted to help and support us after half an hour of talking with us. And before he went, he gave us two cold beers—an amazing gift on a hot day like that. We didn’t even finish our drinks when Oskar was back again, this time holding a bag filled with ice and 8 beer cans. That was definitely too many beers for us, but he wouldn’t take a “no” for an answer; he said that we could give them away if we didn’t want them.

We didn’t have a ping-pong ball to organize a beerpong tournament, so we gave one beer to the first person that came by the laundry, then we took the rest of them to Valery’s place as a thank-you for having us. And even though we didn’t speak a common language with Valery and her mom Anna, we still managed to communicate somehow. We know the Spanish word for beer (cervesa), and we used Google Translate for everything else. Anna worked as a chef for 16 years, and we loved the dinner she made: torta, which is some type of sandwich with meat, avocado, and potato. And we enjoyed the company of their dogs, Nelly and Elvis.

Our initial plan for day 98 was to continue cycling, but Valery invited us to stay one more night; we would go to the beach with Elvis and Nelly. She had to go to work in the morning, so we spent a few hours with Anna, and we also managed to put out a new blog post on our website. And because we finally had wifi, we spent two hours on video call with our families back at home. When Valery came, we went to the beach, and the water was nice but very warm. But the best part was when we took out a frisbee and we spent an hour passing it around and talking. We found out that Valery does speak some English after all, definitely more than we speak Spanish. Our frisbee is the ultimate way of making friends.

Tomorrow we head south again.

Some more pictures: